The boundaries between the feminine and the masculine according to Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio The 14th century is as tumultuous as it is fascinating. The feudal system was beginning to show the first signs of decline, and in urban centres, a new "social class" was proliferating: the bourgeoisie, composed of a heterogeneous group of professionals, artisans, and merchants who could rival the monolithic aristocracy in wealth. This significant shift in economic structure foreshadowed extensive, complex, and intricate social and artistic changes, too vast to be detailed here. However, the figure of Giovanni Boccaccio perfectly embodies this new "upstart" class.

Born in 1313 in Florence or Certaldo, Boccaccio never knew his mother as he was an illegitimate child. However, he grew up under the protection of his father, an ambitious merchant. With a merchant's vision, Giovanni's father tried to establish him as a successful trader, investing without hesitation in his education. Despite being steered, without much success, towards finance and law, Boccaccio did not seem interested in either, as the writer himself stated: "Nature may have endowed others for anything else, but it destined me (and experience attests to it) for poetic meditations, even from my mother's womb, and in my opinion, I was born for that."

Following his father's wishes, Giovanni lived in Naples for 14 years as an apprentice merchant and law student. Despite despising the profession assigned by his father, young Boccaccio did not waste his time. He participated in all possible festivities, lived a dissolute life thanks to his family's wealth, built solid connections, both financial and intellectual, frequented the library and university, and learned Latin, which he boasted about in his old age.

However, Boccaccio's scenario would take a radical turn - ironically, Boccaccio extensively wrote about the Wheel of Fortune and its whims. Upon his return to Florence in 1341, he not only found a city ravaged by the outbreak of the Black Death in 1340 but also witnessed his father's business going bankrupt. During these years, we see Boccaccio trying to adapt to the Tuscan city, forging his intellectual circle, cultivating his writing, and sporadically working in various professions such as diplomat, treasurer, and ambassador. However, after this disastrous event, Boccaccio never enjoyed stable financial circumstances.

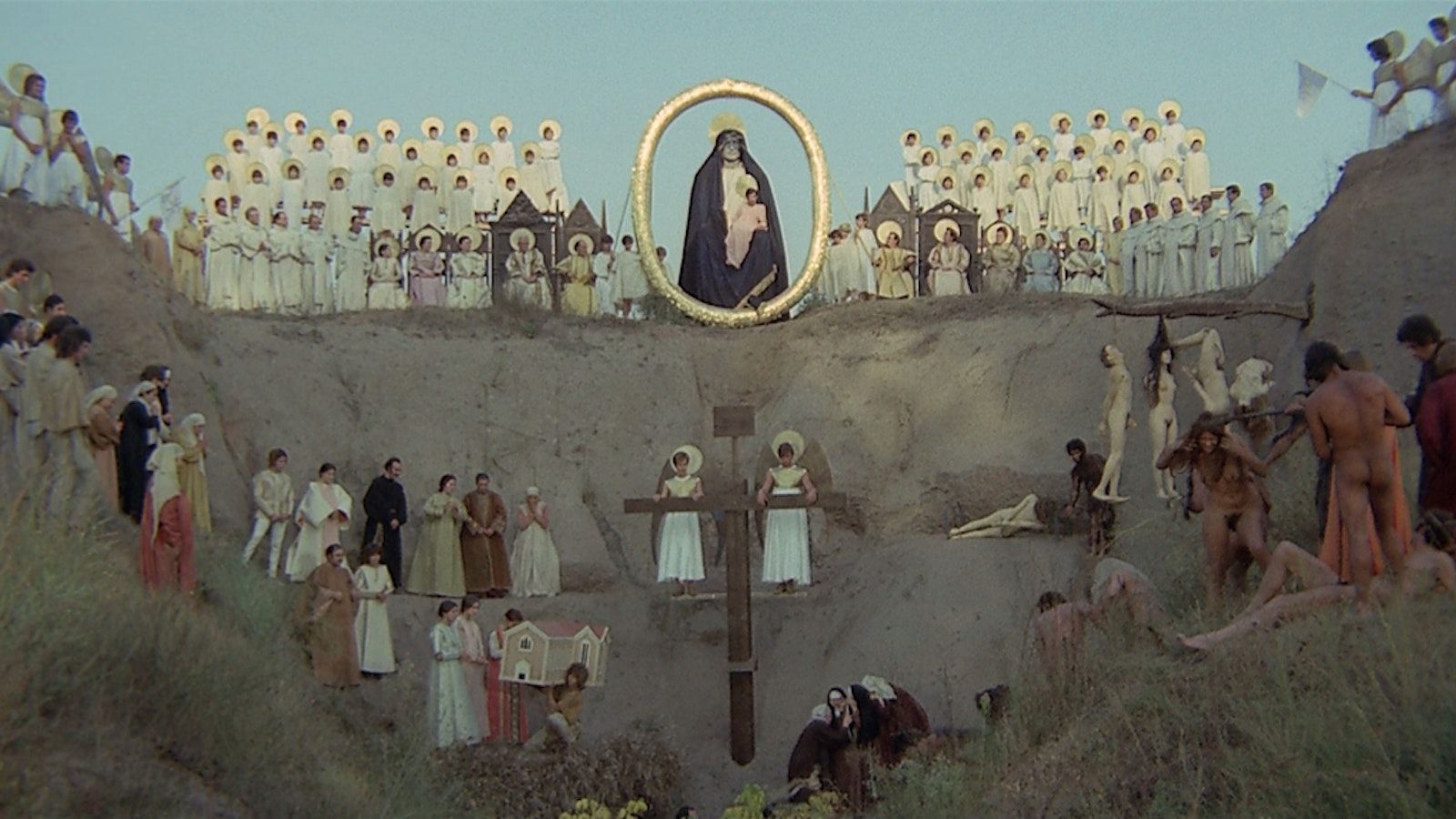

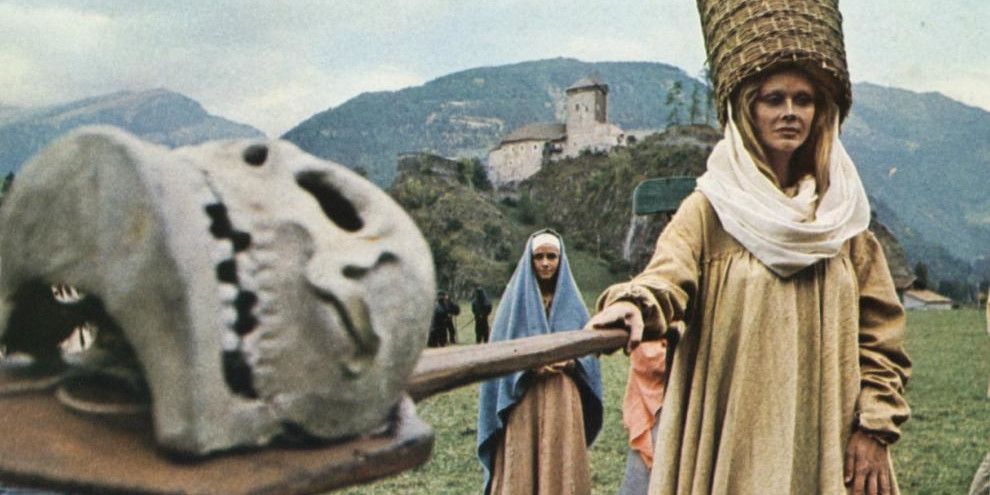

In 1348, the Tuscan writer witnessed another violent attack of the Black Death in Florence. He described it in detail at the beginning of his best-known work, "The Decameron," which was beautifully adapted by Pier Paolo Pasolini.

The writer survived the plague but never escaped his condition as a bankrupt bourgeois. He undertook some jobs, true, and at some point in his life, he could travel without worries and dedicate himself to his literary activity. However, the last years of his life were spent as a dishevelled, weak old man, afflicted by the unsanitary conditions in which he lived, cherishing the fur coat that his faithful friend, the poet Petrarch - aware of his living conditions - had left him before dying. Giovanni Boccaccio died in 1375 in dire poverty. Throughout his life, he had rejected numerous patronage proposals, resigning himself to the caprices of Fortune, which, in his view, were inevitable for any human being.

De Mulieribus Claris

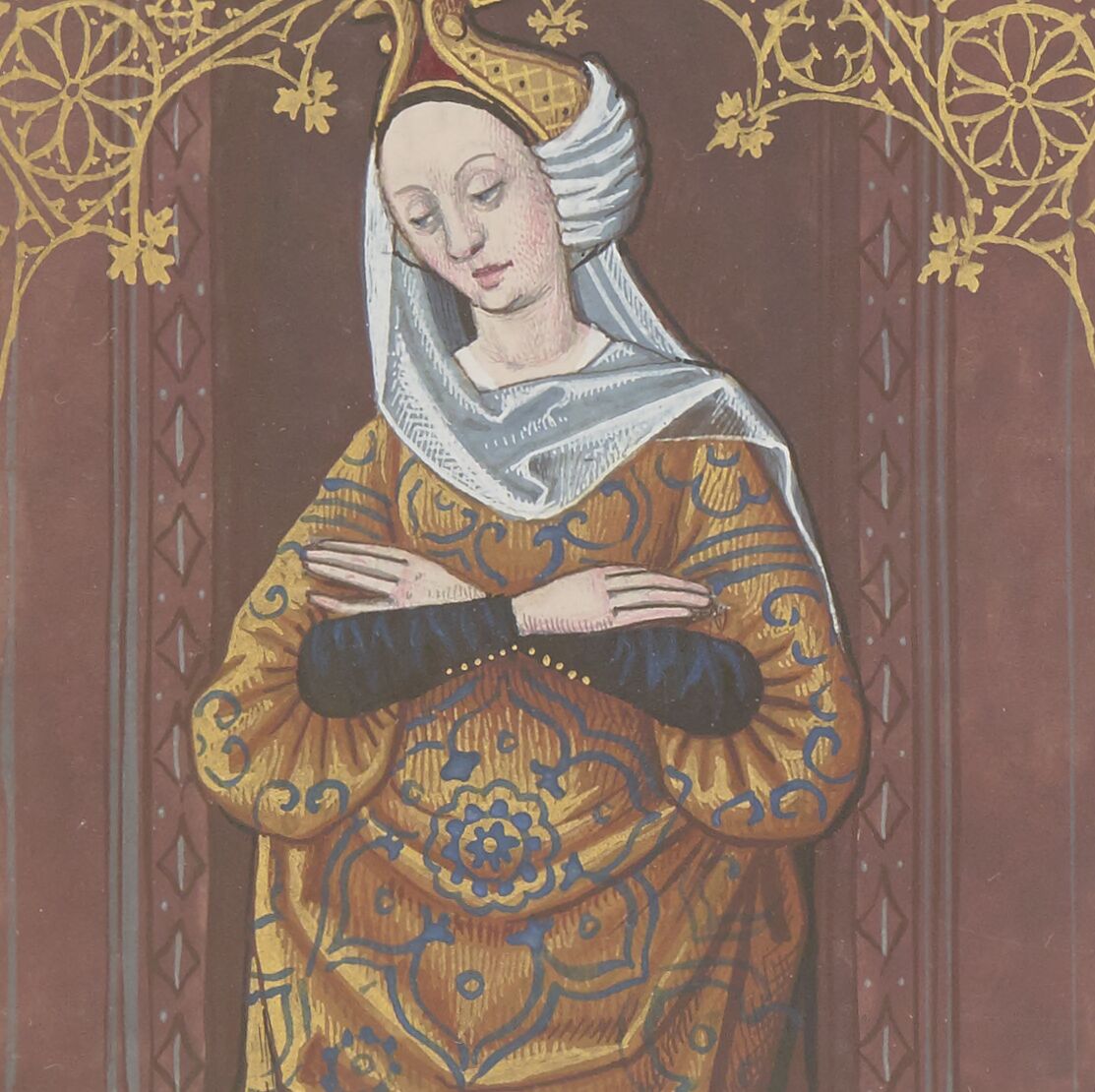

Giovanni Boccaccio dedicated a significant part of his life to compiling and revising "De Mulieribus Claris" or "Famous Women." It is a Latin opus that collects the biographies of 106 "pagan" women, following the style of other works with exemplary biographies. Petrarch had written "De Viris Illustribus" (On Famous Men), and Giovanni himself had dedicated another piece to the biographical genre in "De Casibus Virorum Illustrium" (On the Fates of Famous Men). However, the dedication of an entire volume exclusively to women is noteworthy. Some critics have seen in its writing the author's interest in female characters and an intention to connect with a female audience. However, is that true?

Boccaccio begins his book with what seems like a good declaration of intent: "It has been a long time since some of the ancients wrote profitable books about famous men (…) For those who, to surpass others in illustrious deeds, employed all their effort, their talent, and, if necessary, their blood and soul, deserved to have their names perpetually remembered by posterity. It truly astonishes me how little interest women have aroused among writers, to the extent that they have not enjoyed the favour of any special mention in any work" (we agree, Giovanni, you would be surprised to know that the same thing will happen seven centuries later).

However... alas! It only takes two more lines to disappoint us: "And if men are worthy of praise for carrying out great deeds with the strength given to them, how much more so are women, to whom nature endowed (almost all) with a weak and feeble body and a dull mind?" and he continues: "I think that the actions of these women will please not only men but also women themselves since they, more often than not, are ignorant of history and need a more detailed explanation." In summary: 1. For Boccaccio, notable women are such an unusual and extraordinary fact that it justifies writing the book. 2. Since women know less, everything must be explained to them in detail. And if anything remained unclear, Boccaccio includes counterexamples, that is, women who stand out for their negative qualities, as a way, he says, to show avoidable moral behaviours. It is precisely in these counterexamples that the most interesting characters are found.

Weakness and Stupidity

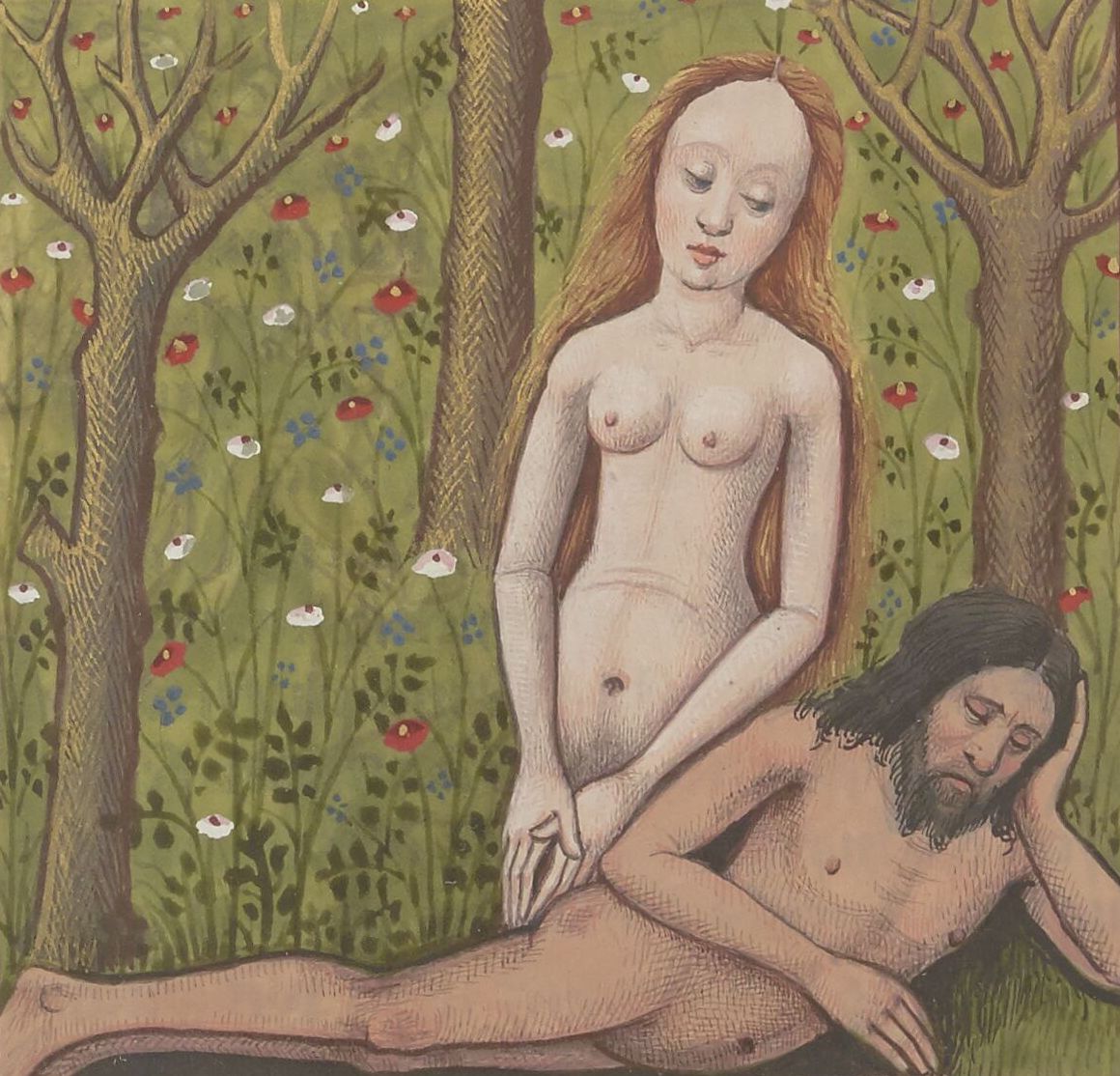

For Boccaccio, as he clearly states in the prologue, women are essentially weak, with catastrophic consequences. Due to Eve's weakness and "stupidity", the rest of the mortals "were born for pain."

The case of Ceres, the goddess of harvest, is quite intriguing. Boccaccio admits not knowing whether to "praise or censure her talent" because, thanks to agriculture, "the fields, once common, became private properties surrounded by ditches and fences, the concerns of agriculture arose, and mortal beings assumed the toils."

Boccaccio often emphasizes the inherent stupidity of women, even when he intends to praise one of his heroines. Regarding Nicaula, the queen of Ethiopia, he states that she "did not devote herself to idleness and feminine softness (…) but was endowed with knowledge." Similarly, when mentioning the painter Irene, he states: "I think she deserves praise because it is a difficult profession for a woman since it cannot be achieved without a very strong talent, which in women usually appears very late." He refers similarly to the painter and sculptress Marcia, who "disdained feminine tasks and idleness."

Boccaccio's venom gushes out when it comes to Sabina Popea, the wife of Nero, who her husband murdered. Boccaccio approves of the tragic end of the heroine and concludes her story with a moralizing reading: "Regarding Popea's fortune, I could say something against excessive idleness, softness, petulance, and tears of women, very true and very pernicious poison for those who believe in them. But I will refrain from expressing it so as not to appear as if I have written a satire instead of a history."

Perfidy

On the other hand, female intelligence can also be alarming. Obviously, it could be equally destructive in the hands of a woman - due to her weak spirit. This enters the realm of cunning, manipulative, and ambitious women.

Of Medea, Boccaccio claims she is the "cruel example of ancient perfidy," although she was "beautiful and skilled in sorcery." In the case of the sorceress Medea, we can precisely glimpse who the book is intended for. In his warning to men, Giovanni writes: "Foolish are the eyes that are attracted, trapped, captivated, and held with exciting lures by beauty." Thus, the beauty of the faithless woman becomes a threat to be protected against. Boccaccio insists on the destructive nature of the beauty-intelligence combination.

Notable is the case of Yole, daughter of the king of Aetolia. The princess had been promised to the famous Hercules, but at the last moment, her father rejected the marriage. A furious Hercules killed Yole's father (which Boccaccio does not find objectionable). However, the young princess, "eager for revenge," planned a curious counterattack: with "flattering words and deceptive audacity (…) she avenged her father's death not with weapons but with deceit and lasciviousness." And what did she do? Did she kill him? No, something much worse: "she first ordered him to adorn his fingers with rings, smooth his tousled head with ointments from Cyprus (…) and forced him to perform women's tasks," thereby weakening "the dignity of such a powerful man with lasciviousness more than if she had killed him with poison or a sword." In short, according to Boccaccio, femininity is worse than death.

Pride

Pride is another attribute frequently associated with femininity. I will highlight the case of Niobe, the queen of Thebes. According to Boccaccio, the queen experienced days of glory and also had fruitful offspring, no less than seven sons and seven daughters. This made the queen arrogant, defying the gods themselves, and she was severely punished as a result. A plague killed all her children, and her husband, driven mad by the loss, took his own life. Boccaccio seizes this dramatic climax to warn that Niobe's mistake was thinking she was responsible for her offspring, not nature or fortune. Thus, the queen arrogantly challenged the divine powers by not attributing her fertility to them. Boccaccio concludes: "It is hard and odious, I will not say to tolerate but even to contemplate arrogant men, but arrogant women are annoying and unbearable. Men have an ardent spirit by nature, but women, due to their weak intellect and little virtue, are more suited for luxuries than for ruling."

Lust

Giovanni Boccaccio's friend, Petrarch, lovingly reproached him for frequently succumbing to the "flames of sensuality." Additionally, as far as we know, Giovanni had five illegitimate children. However, lust is the most frequent admonition towards women in his work. There are many heroines whom Boccaccio accuses of being lascivious and adulterous. However, if there is one woman who embodies all vices from the writer's perspective, it is Cleopatra. He begins by affirming that "she resorted to crime to reign and had no merits other than reaching the throne and the beauty of her face. Instead," she became renowned throughout the world for her greed, cruelty, and lust" or "Enflamed by the ambition to reign, Cleopatra poisoned her innocent young husband, her fifteen-year-old brother."

This woman, "born in wickedness," seduced the powerful Julius Caesar: "she reached him and promised herself the kingdom if she could conquer the conqueror of the world with her lust, for she was extremely beautiful and seduced whomever she wanted with the art of the sparkle in her eyes and her eloquence." Once established on the throne, Boccaccio portrays Cleopatra using a classic formula in the damnatio memoriae of queens; it is an uncontrolled greed that could be identified with lust, in other words, an insatiable excess that oscillates between sexual and material appetite: "she dedicated herself to her voluptuousness, almost becoming a prostitute of an oriental kingdom, greedy for gold and jewels. With her arts, she not only left her lovers ruined but also plundered and left the Egyptian temples and sacred places empty of vases, statues, and other treasures" (those who have read the previous newsletter will recognize the Whore of Babylon here). Cleopatra is, ultimately, the paradigm of a vampiric woman who leaves her lovers "ruined." It is understood that this ruin is, evidently, physiological.

After Caesar's death, the unstoppable queen seduced another Triumvirate member: Mark Antony, whom she manipulated (once again, thanks to her lust) to grant her "Syria and Arabia." After the fall of Alexandria, "Cleopatra tried in vain, with her old talent that had previously succeeded in seducing Caesar and Antony with her concupiscent desires, also to seduce the young Octavian." However, humiliated by the loss of political weight, she and her lover Mark Antony committed suicide: "she opened her veins and placed asps in the wounds. It is said that these snakes induce the sleep of death." Boccaccio approves, as he will on other occasions, the suicide of the treacherous queen because only in this way "the wretched one accepted the end of her avarice, her lust, and her life."

The suicide of Cleopatra was the subject of multiple speculations. Boccaccio himself provides several versions, joining the speculative tradition surrounding her death. In the 13th century, the General Estoria by the Spanish king Alfonso X the Wise (1221-1284) included two versions: one depicted Cleopatra placing the snakes in her veins, and the other in her breasts. Cleopatra's body had become a symbolic space, an eroticized yet disdainful place that embodied terror, desire, vice, and punishment.

Illustrious women

Boccaccio reserves some words for those women he considers illustrious. They are primarily selfless women, sacrificed, often martyrs, and, of course, chaste. Among them is Dido, the queen of Carthage, who, upon becoming a widow, "decided to die rather than violate her chastity" and committed suicide with a knife in front of her subjects. There is also the Roman Lucretia, who, after being raped, decided to sacrifice herself, uttering these words: "I absolve myself of the sin, but I cannot escape the punishment, and henceforth no dishonourable woman shall live with Lucretia as an example." Clearly, the Tuscan writer readily accepted female suicides.

The Italian author mentions a "young Roman woman" whose name he admits not knowing, but he praises her piety and nobility. The anonymous girl's mother was sentenced to death, and while awaiting her sentence in prison, her daughter fed her with her own milk. The gesture moved the council, who permanently released the woman. Boccaccio concludes: "For such a pious act, a garland made of flowers is not sufficient."

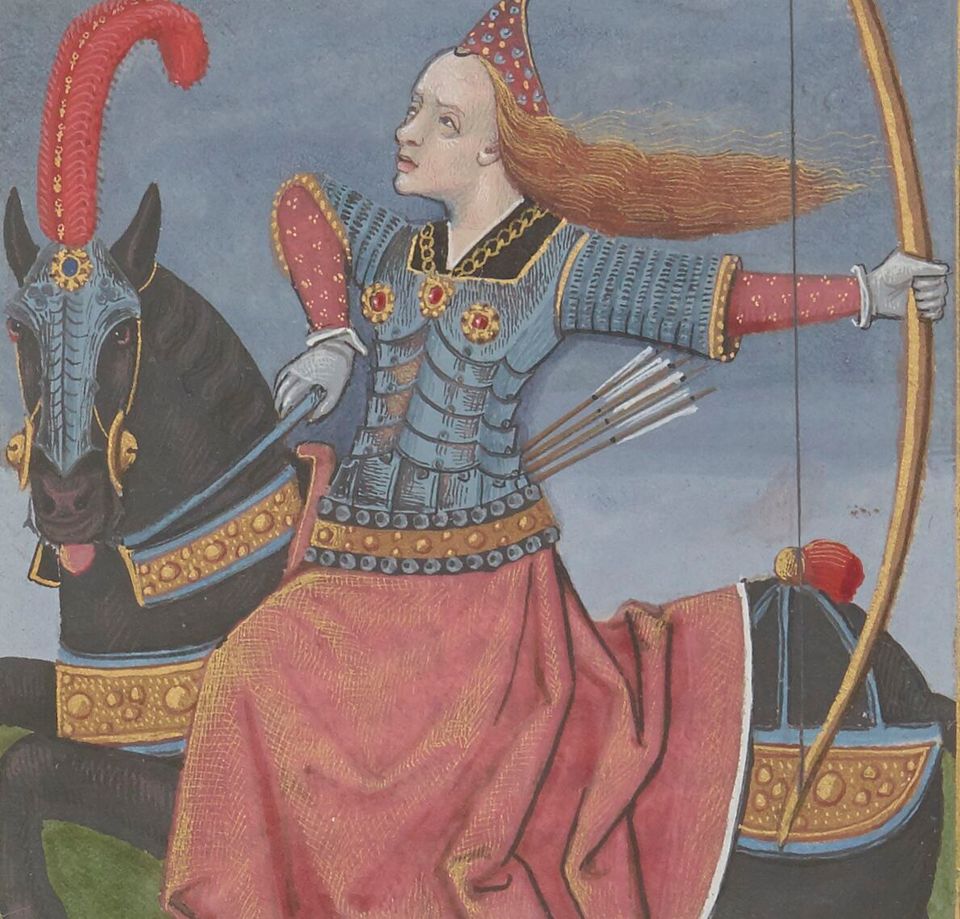

Finally, Boccaccio surprises by praising, in three separate chapters, the women he truly seems to admire: the Amazons. He dedicates two chapters to the sisters Marpesa and Lampedonia. These daughters of Mars took up arms after being widowed due to the plundering of an enemy army. They fought so fiercely against male enemies that the latter had no choice but to retreat. Once they established their political position, these warrior women procreated with men from a neighbouring tribe: "They would kill male infants immediately and carefully train the females for warfare. Even at a tender age, they would hinder the growth of their right breast using fire or some drug so that it would not hinder their adult proficiency in archery. They kept their left breast intact to nourish their offspring, which is why they were called Amazons. As they grew up, they did not educate the girls as we do ours, for they rejected sitting at the spinning wheel and other feminine tasks. On the contrary, through hunting, raiding, horse taming, working with weapons, arrows, and other similar exercises, they continuously strengthened the girls' skills and manly strength."

A few chapters later, he mentions the daughters of Marpesa, Oritia, and Antiope. He praises their warrior and strategic abilities and the expansion of their empire. However, we must advance a few more chapters to find their successor, Penthesilea, for whom Boccaccio shows excellent devotion. He states that she acted with "greatness and masculinity" and reveals the reason for his profound admiration. For the author, these warriors are admirable because of their degree of masculinity: "Some admire women who, armed, dare to fight with men, but that admiration diminishes when we consider that habit changes nature. Thus, Penthesilea and those like her become, through weapons, more manly than those whom nature made male through sex but who, due to idleness and sloth, become like women or hares with helmets."

More than a collection of illustrious biographies, Boccaccio's treatise attempts to define the feminine and the masculine, both understood as a polarity. It is a hierarchical polarity, where greatness resides in masculinity while weakness lies in the feminine. Boccaccio thus reflects a perspective that was quite widespread throughout the Middle Ages and propagated by physicians, philosophers, and theologians. In that sense, Boccaccio's treatise does not possess the modernity that some scholars have wanted to attribute to it but instead inherits a well-established misogynistic tradition in 14th-century thought. The women admired by Boccaccio are those whose sacrifices lead to martyrdom, chaste women, and primarily those who possess masculine qualities. Some authors have seen "De Mulieribus Claris" as a warning directed towards a male audience against female perversity, which often begins with beauty. Undoubtedly, it is not a treatise written for a female audience, and there may be a moralizing intention towards masculinity, including Boccaccio himself, who, as we know, was not precisely insensitive to female beauty.

In my opinion, such a moralizing intention may exist. However, Boccaccio is primarily contributing to a debate of great importance at that time: the division between the masculine and the feminine, with their corresponding qualities, responsibilities, and burdens. The work of the Italian writer is not only an ode to masculinity but also a reminder of the place that femininity should occupy. Let us not forget that we are in a historical context of a tremendous demographic crisis due to the Black Death. An event that forced many theorists to reconsider reproductive issues and, consequently, matters related to sex and gender. Unsurprisingly, legislation against abortion and contraceptive methods intensified during this period due to the declining population. This compelled many treatise writers to address topics such as the body, sex, and gender, attempting to draw dividing lines between them and attributing moral implications to physiological matters. Although Boccaccio considered himself a historian, he was participating in a discussion of great importance at that time: the boundaries between the feminine and the masculine.

(Images from BnF ms. Français 599, 1400-1467)

Member discussion