Chemical Chronicles: A Controversial Discipline's Turning Point

Dear Subscribers,

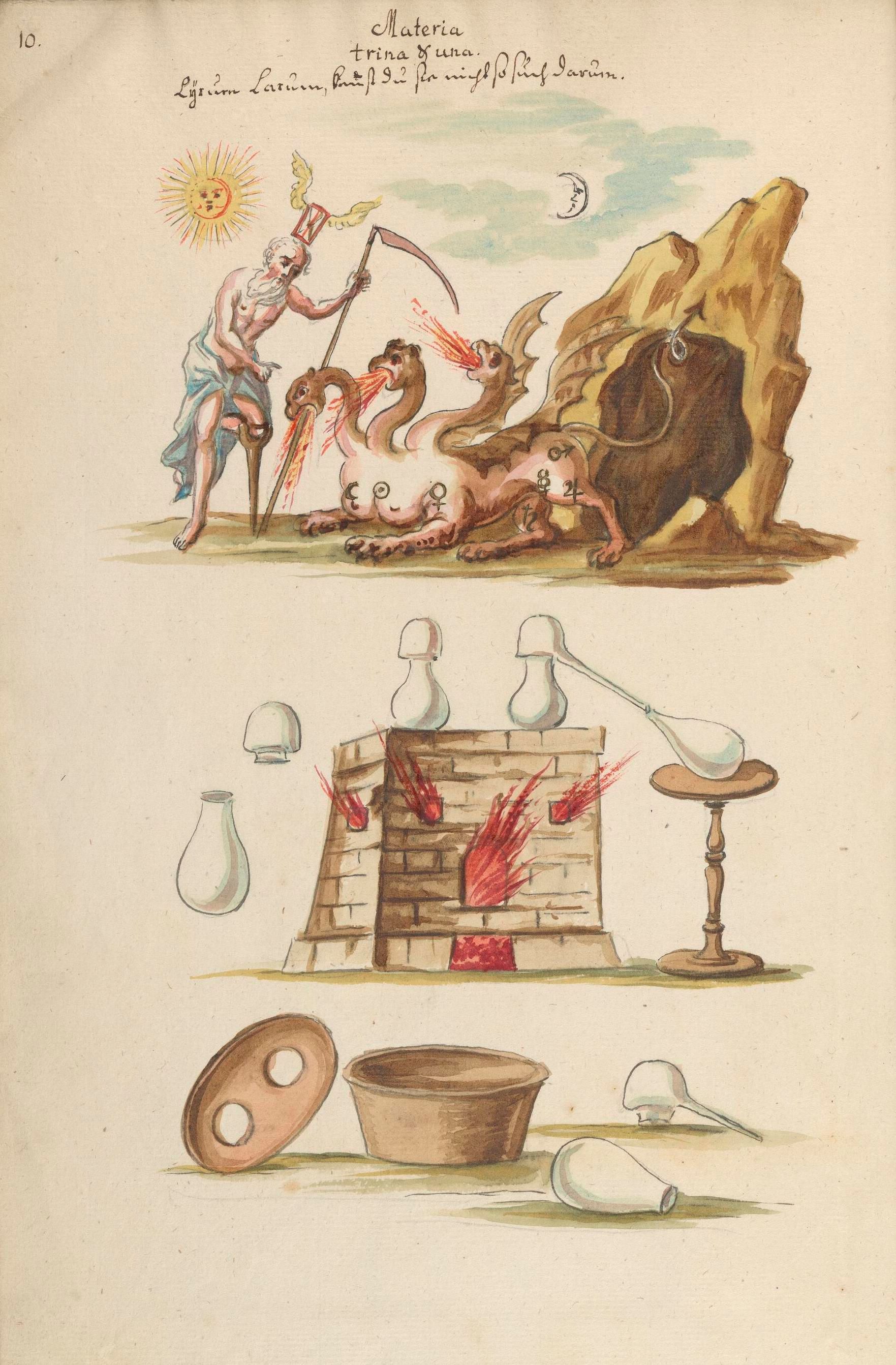

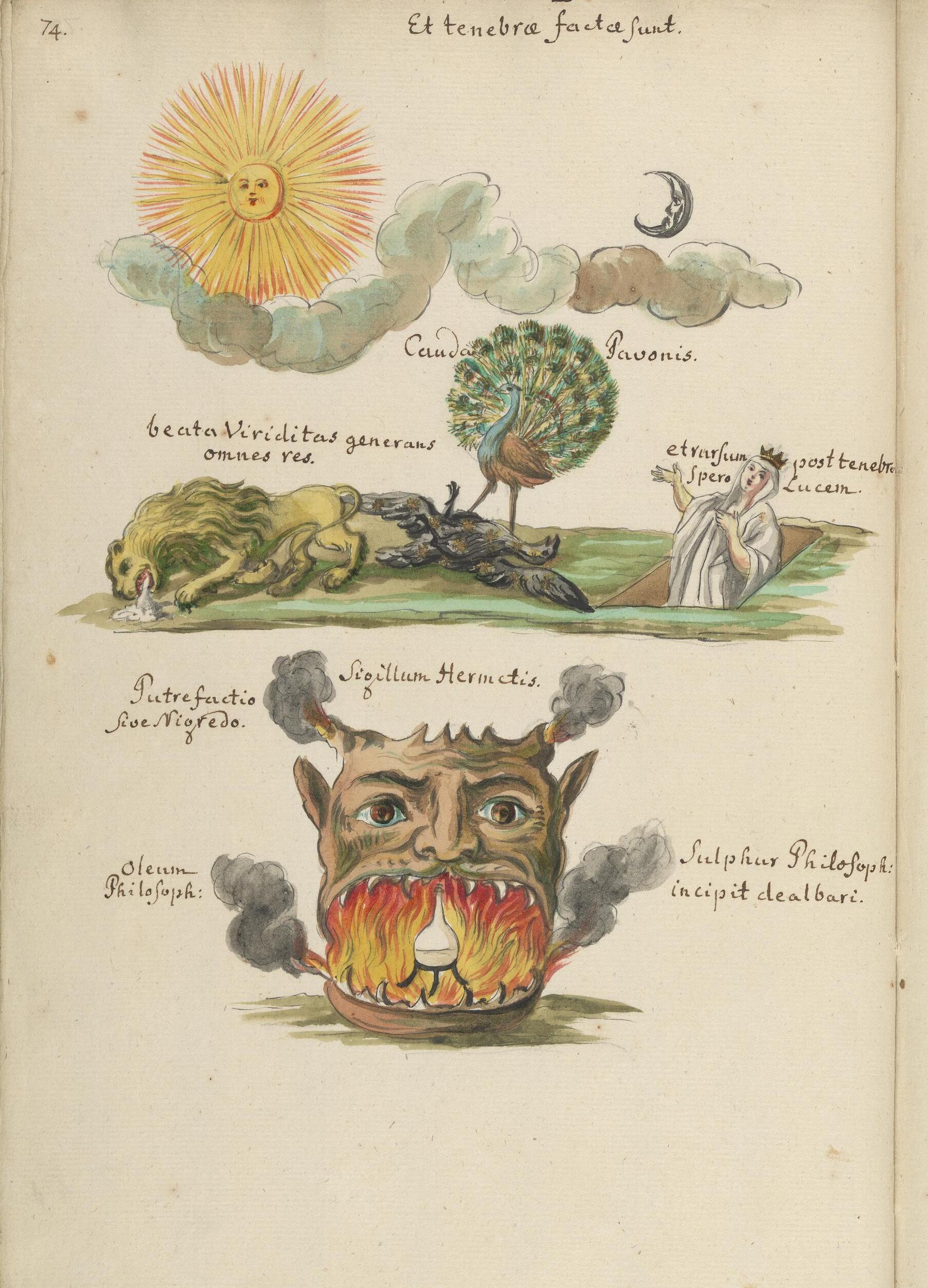

Many of you have requested a brief introduction to the basic concepts of alchemy and its imagery. Therefore, I have decided to dedicate this month's newsletters to some aspects related to European alchemy. This won’t be a history of alchemy as that would be impossible to cover in a newsletter; however, I will focus on the most contentious aspects of the mercurial science, for nothing defines it better than its inherent tensions. In this regard, I wish to focus on an episode that encapsulates all the violence and contradictions of alchemy: the moment when alchemy and chemistry decided to “divorce” and operate as independent terms. This occurred in France in the 17th century, although it was a crisis that had been looming in previous centuries. We will delve much deeper into alchemy in this newsletter, so fret not if you don’t find all the information in this instalment; there will be more, much more…

Please do not hesitate to send me suggestions about the alchemical topics you are most interested in!

María

The Twilight of Alchemy

Nowadays, alchemy evokes occultist imagery, a universe inhabited by necromancers or a symbolic language full of intricate psychological and spiritual processes. However, before the 17th century, alchemy was a tangible discipline practised in (malodorous) and far from glamorous laboratories. It had very specific objectives, sought material outcomes and often was much more mundane than we tend to believe.

When contemplating alchemy, we must leap chronologically and transport ourselves to the meaning this discipline bore before the 17th century. Towards the end of this century, we witnessed its break with academia and its subsequent split from chemistry. Until then, “chemistry” and “alchemy” were indistinguishable terms; they appear interchangeable in most medieval and subsequent alchemical treatises. At the twilight of the 16th century, Stanihurst, one of the alchemists at the court of Spanish monarch Philip II, wrote: “Both words signify the same thing.” Large alchemical compilations boast titles like Theatrum Chemicum (1602), and a century later, in 1702, the term chemica was still used as a synonym for chrysopoeia judging by the title of the grand anthology Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa.

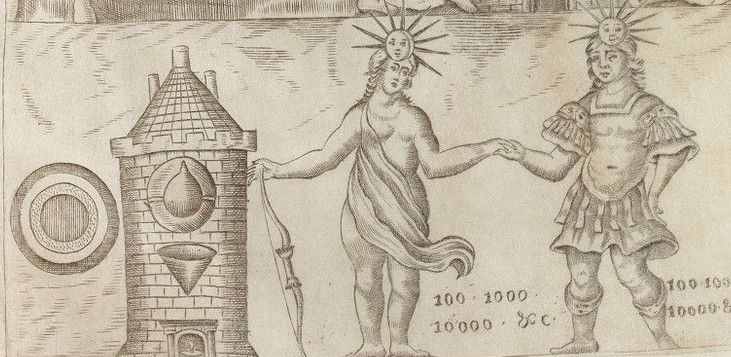

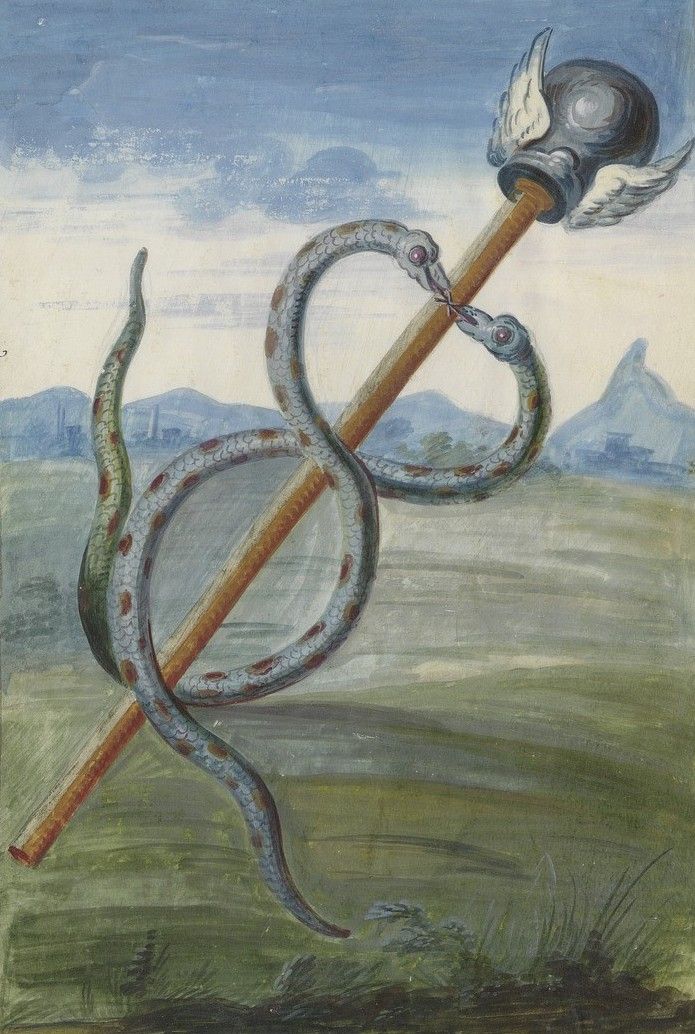

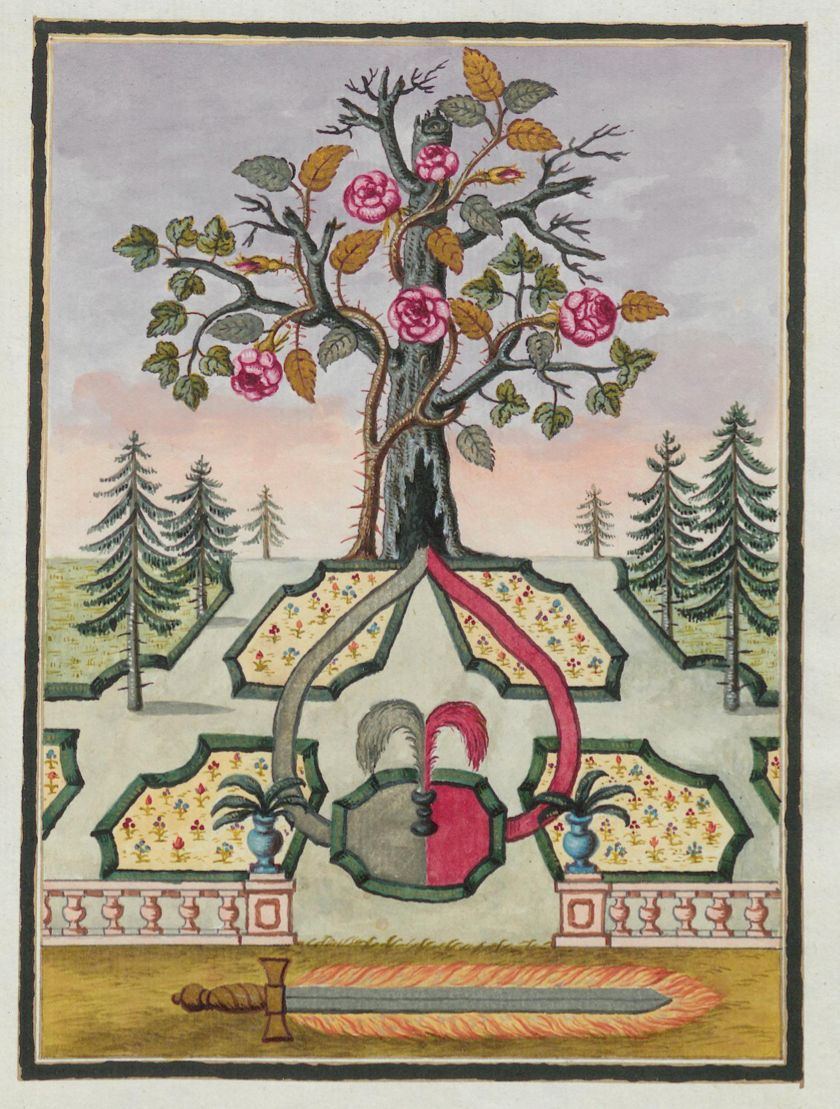

It was in 1666 when the entrepreneur and politician Jean-Baptiste Colbert convinced the King of France, Louis XIV, to establish the Académie des Sciences. Interestingly, upon its foundation, Colbert explicitly prohibited two practices: astrological divination and any attempt to produce the Philosopher’s Stone. The entry of chemistry (or alchemy) into the strait-laced French academia posed several problems. Indeed, alchemy was a controversial and exceedingly versatile discipline. Although its basic principle was simple—transforming the essence of natural substances through fire—its offshoots and interpretations were highly complex. Under the name of alchemy, practices were diverse, such as medicine, pharmacology, the manufacture of cosmetics, elixirs, tinctures, poisons, and perfumes, the forgery of precious stones, pyrotechnics, the manufacture of mirrors, and the transmutation of metals into gold with the help of the Philosopher’s Stone. Despite all of them having in common two principles intrinsic to alchemy, transformation and fire, they were, in reality, very diverse and often conflicting practices. The bone of contention was, and always will be, the Philosopher's Stone, a “stone that is not a stone,” a substance theoretically obtained through an alchemical process promising to transform metals into silver or gold (transmutation).

The Transmutation

Both chrysopoeia (transmutation of metals into gold) and the Philosopher’s Stone have always been controversial at the heart of alchemy. Avicenna (980-1037) denied the possibility of alchemists being able to alter the “essence of species.” In the 13th century, al-Jawbari wrote The Unveiling of Secrets, revealing the tricks charlatans executed. In the 14th century, Pope John XXII prohibited the practice of alchemy, claiming it “promised what it could not deliver.” In the 16th century, the Aragonese theologian Monreal termed it a “ruinous doctrine.”

In this sense, the French academy merely prolonged a debate that had existed for centuries. In fact, due to the vehement attacks and notable public executions, many alchemists “initiated in the true art” had been forced to unmask the charlatans, thus establishing a clear division between the true knowers and the fraudsters. An example of this is the work written by the alchemist Richard Stanihurst, dedicated to Philip II (1527-1598), with the aim that the monarch could identify deceivers immediately. It bears an illustrative title: The Touch of Alchemy, in which the true and false effects of the art are declared and how the false practices of deceivers and vagabond tricksters will be recognized.

Paradoxically, the creation of gold was as persecuted as it was coveted. Many monarchs and lords oscillated between relentless persecution and personal financing of laboratories. It was common for the same monarchs who prohibited alchemy to provide, at the same time, specific licenses to practice it as long as they could benefit from the results. Although documentation is not very clear in this regard – after all, financing transmutations was something done with certain secrecy – between the 14th and 17th centuries, alchemy found its source of funding in the main European courts. It is known that Joan I of Aragon (1350-1395) welcomed several alchemists to his court; paradoxically, one of them, Jaume Lustrach, was later imprisoned by Joan's successor, Martin of Aragon. With a kingdom in bankruptcy, Philip II financed a laboratory to fill his coffers. However, correspondence with his secretary shows how the experiments did not bear fruit, and gradually, the monarch lost hope. Some alchemists benefited from such patronages in England, France, Italy, Flanders, Germany, Sweden, and Bohemia. They practised the golden art and developed sophisticated systems to appease the impatience of their lords. Some alchemical treatises advise how to react to imminent punishment: prudence and ambiguous language. It's not hard to imagine that this matter was difficult to manage for the spheres of power. If the creation of gold was true, it could devalue the precious metal, leading many kingdoms to bankruptcy.

On the other hand, if it was just a falsification, it was also economically unsustainable. In reality, it was a matter of monetary character. As we will see in other newsletters, alchemy also entailed other moral and theological problems. However, I would say that the financial issue carried the most weight in its legislative hostility.

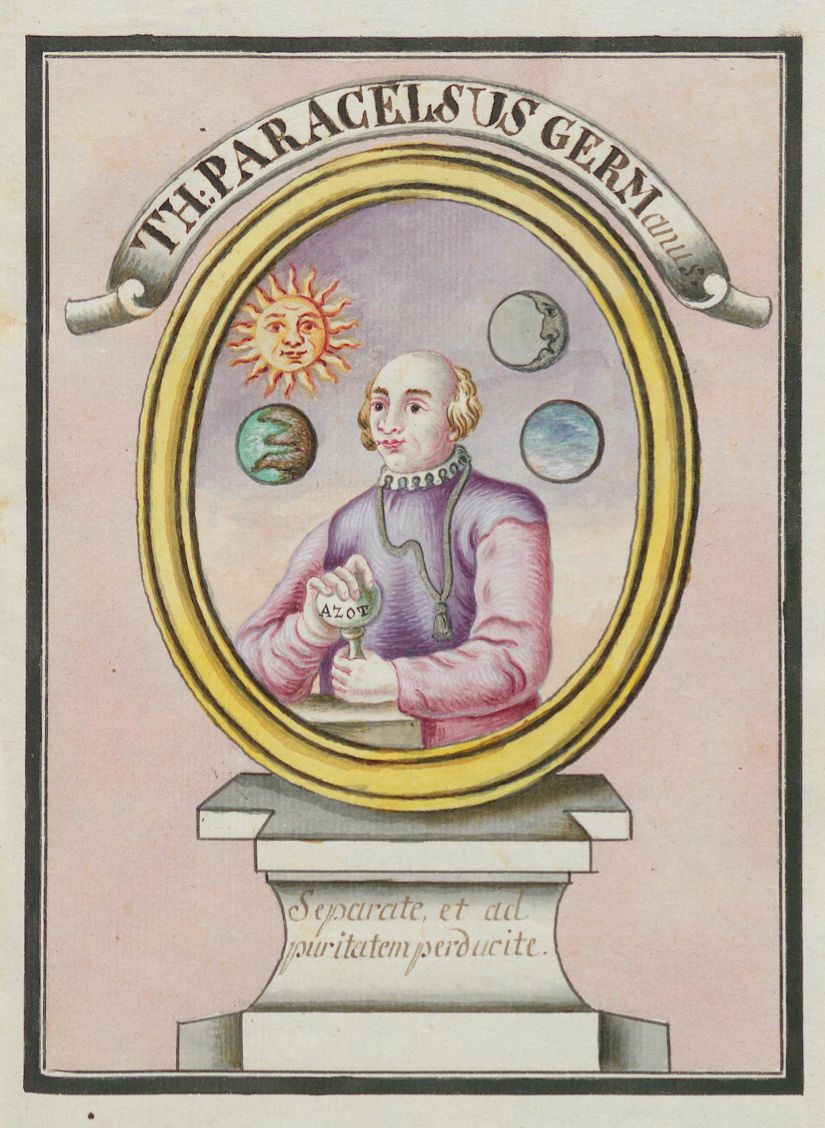

However, under the shelter of the scientific optimism of 1700, all of that belonged to an obsolete universe. In other words, it referred to superstition and obscurantism. An alchemist could only be a madman or an impostor; evidently, neither could have a place in the French academy. It mattered little that alchemy or chemistry had been extremely versatile; transmutation had overshadowed the rest of the disciplines, and although many alchemists, like Paracelsus, had denied the possibility of transmutation, in the minds of many academics, alchemy was merely a tool of lunatics seeking the creation of gold.

From its foundation in 1666 until 1700, the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris prohibited the transmutation of metals at least three times. Interestingly, as Lawrence M. Principe pointed out, these restrictions did not come from the chemists themselves but from other academics (mathematicians). In an institution aspiring to present itself at the forefront of scientific advancement, alchemy (or chemistry) was an embarrassing element. The lovers of exact sciences felt secondhand embarrassment for their chemical colleagues. Therefore, between 1666 and 1722, and after many disputes in the French academy, chemists were more or less coerced to publicly denounce practices like transmutation or concepts like the Philosopher's Stone. In this context, the chemist Étienne-François Geoffroy published a text in 1722 titled On the Superstitions regarding the Philosopher's Stone to unmask the fraudulent activities of alchemists and, more specifically, the practice of transmutation. The idea was to extirpate the uncomfortable elements of chemistry, place them in another category (alchemy), and solidify its scientific dimension, making it more digestible for the academy—basically, a rebranding. Thus, terminologies began to be delimited: alchemy and chemistry were now used with different meanings. This late schism differentiates chemistry, as a science executed by professionals and academic researchers, from alchemy, a marginal pseudoscience whose sole objective is transmuting metals into gold. However, it is essential to insist that this schism is a modern paradigm and does not represent the alchemical practice of previous centuries, which is much more heterogeneous, rich, and plural than what tends to be described.

Member discussion